The

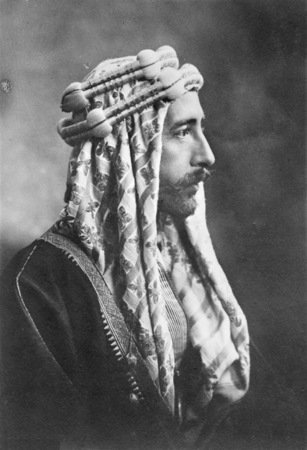

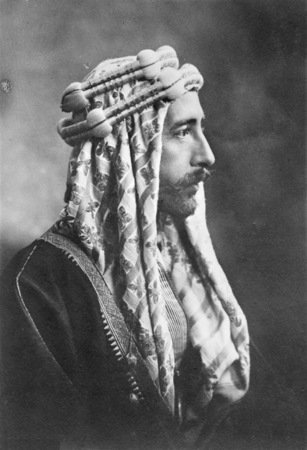

Faisal–Weizmann Agreement was signed on 3 January 1919, by

Emir Faisal (son of the King of

Hejaz), who was for a short time King of the Arab Kingdom of Syria or Greater Syria in 1920, and was King of the Kingdom of Iraq from August 1921 to 1933, and

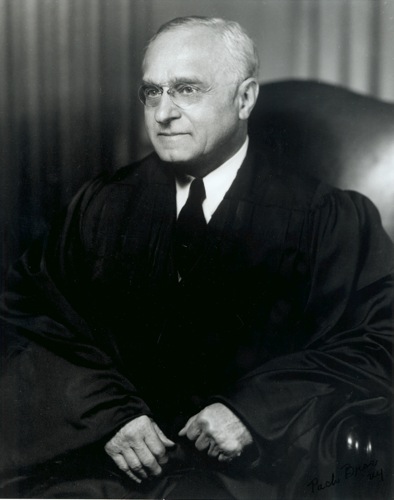

Chaim Weizmann (later President of the

World Zionist Organization) as part of the

Paris Peace Conference, 1919 settling disputes stemming from World War I. It was a short-lived agreement for Arab–Jewish cooperation on the development of a Jewish homeland in

Palestine and an Arab nation in a large part of the Middle East.

One or more of the Allies may have suggested that a representative of the Zionist Organization secure the agreement. The secret

Sykes–Picot Agreement had called for an "Arab State or a Confederation of Arab States ... under the suzerainty of an Arab chief." The French and British also proposed an international administration, the form of which was to be decided upon after consultation with Russia, and subsequently in consultation with the other Allies, "and the representatives of the Shereef of Mecca."

[1]

1918. Emir Faisal I and Chaim Weizmann (left, wearing Arab headdress as a sign of friendship)

Overview

Weizmann first met Faisal in June 1918, during the British advance from the South against the

Ottoman Empire in World War I. As leader of an impromptu "Zionist Commission", Weizmann traveled to southern Transjordan for the meeting. The intended purpose was to forge an agreement between Faisal and the

Zionist movement to support an Arab Kingdom and Jewish settlement in Palestine, respectively. The wishes of the Palestinian Arabs were to be ignored, and, indeed, both men seem to have held the Palestinian Arabs in considerable disdain. Weizmann had called them "treacherous", "arrogant", "uneducated", and "greedy" and had complained to the British that the system in Palestine did "not take into account the fact that there is a fundamental qualitative difference between Jew and Arab".

[2] After his meeting with Faisal, Weizmann allegedly reported that Faisal was "contemptuous of the Palestinian Arabs whom he doesn't even regard as Arabs".

[3]

In preparation for the meeting, British diplomat

Mark Sykes had written to Faisal about the Jewish people, "I know that the Arabs despise, condemn, and hate the Jews" but he added "I speak the truth when I say that this race, despised and weak, is universal, is all-powerful and cannot be put down" and he suggested that Faisal view the Jews as a powerful ally.

[4] In the event, Weizmann and Faisal established an agreement under which Faisal would support close Jewish settlement in Palestine and reestablish their dominion, while the Zionist movement would assist in the development of the vast Arab nation that Faisal hoped to establish.

At their first meeting in June 1918 Weizmann had assured Faisal that "the Jews did not propose to set up a government of their own but wished to work under British protection, to colonize and develop Palestine without encroaching on any legitimate interests".

[5]Weizmann and Faisal met again later in 1918, while both were in London preparing their statements for the upcoming

peace conference in Paris.

They signed the written agreement, which bears their names, on 3 January 1919. The next day, Weizmann arrived in Paris to head the Zionist delegation to the Peace Conference. It was a triumphal moment for Weizmann; it was an accord that climaxed years of negotiations and ceaseless shuttles between the Middle East and the capitals of Western Europe and that promised to usher in an era of peace and cooperation between the two principal ethnic groups of Palestine: Arabs and Jews.

[6]

Map showing the boundaries of Palestine proposed by Zionists at the Paris Conference, superimposed on modern boundaries.

[citation needed]

Background

Henry McMahon had

exchanged letters with Faisal's father

Hussein bin Ali, Sharif of Mecca in 1915, in which he had promised Hussein control of

Arab lands with the exception of

"portions of Syria" lying to the west of

"the districts of Damascus, Homs, Hama and Aleppo". Palestine lies to the south of these areas and wasn't explicitly mentioned. That modern-day Lebanese region of the

Mediterranean coast was set aside as part of a future French Mandate. After the war the extent of the coastal exclusion was hotly disputed. Hussein had protested that the Arabs of

Beirut would greatly oppose isolation from the Arab state or states, but did not bring up the matter of

Jerusalem or Palestine. Dr.

Chaim Weizmann wrote in his autobiography

Trial and Error that Palestine had been excluded from the areas that should have been Arab and independent. This interpretation was supported explicitly by the

British government in the

1922 White Paper.

On the basis of McMahon's assurances the

Arab Revolt began on 5 June 1916. However, the British and French also secretly concluded the

Sykes–Picot Agreement on 16 May 1916.

[7] This agreement divided many Arab territories into British- and French-administered areas and allowed for the internationalization of Palestine.

[7] Hussein learned of the agreement when it was leaked by the new Russian government in December 1917, but was satisfied by two disingenuous telegrams from Sir

Reginald Wingate, High Commissioner of Egypt, assuring him that the British government's commitments to the Arabs were still valid and that the Sykes-Picot Agreement was not a formal treaty.

[7]

According to Isaiah Friedman, Hussein was not perturbed by the Balfour Declaration and on 23 March 1918, in

Al Qibla, the daily newspaper of Mecca, attested that Palestine was "a sacred and beloved homeland of its original sons," the Jews; "the return of these exiles to their homeland will prove materially and spiritually an experimental school for their [Arab] brethren." He called on the Arab population in Palestine to welcome the Jews as brethren and cooperate with them for the common welfare.

[8] Following the publication of the Declaration the British had dispatched Commander

David George Hogarth to see Hussein in January 1918 bearing

the message that the "political and economic freedom" of the Palestinian population was not in question.

[7] Hogarth reported that Hussein "would accept an independent Jewish State in Palestine, nor was I instructed to inform him that such a state was contemplated by Great Britain".

[9] Continuing Arab disquiet over Allied intentions also led during 1918 to the British

Declaration to the Seven and the

Anglo-French Declaration, the latter promising "the complete and final liberation of the peoples who have for so long been oppressed by the Turks, and the setting up of national governments and administrations deriving their authority from the free exercise of the initiative and choice of the indigenous populations."

[7][10]

Lord Grey had been the

foreign secretary during the McMahon-Hussein negotiations. Speaking in the

House of Lords on 27 March 1923, he made it clear that he entertained serious doubts as to the validity of the British government's interpretation of the pledges which he, as foreign secretary, had caused to be given to Hussein in 1915. He called for all of the secret engagements regarding Palestine to be made public.

[10] Many of the relevant documents in the National Archives were later declassified and published. Among them were the minutes of a Cabinet Eastern Committee meeting, chaired by

Lord Curzon,which was held on 5 December 1918. Balfour was in attendance. The minutes revealed that in laying out the government's position Curzon had explained that:

"Palestine was included in the areas as to which Great Britain pledged itself that they should be Arab and independent in the future".

[11]

The agreement

Main points of the agreement:

- The agreement committed both parties to conducting all relations between the groups by the most cordial goodwill and understanding, to work together to encourage immigration of Jews into Palestine on a large scale while protecting the rights of the Arab peasants and tenant farmers, and to safeguard the free practice of religious observances. The Muslim Holy Places were to be under Muslim control.

- The Zionist movement undertook to assist the Arab residents of Palestine and the future Arab state to develop their natural resources and establish a growing economy.

- The boundaries between an Arab State and Palestine should be determined by a Commission after the Paris Peace Conference.

- The parties committed to carrying into effect the Balfour Declaration of 1917, calling for a Jewish national home in all of Palestine.

- Disputes were to be submitted to the British Government for arbitration.

Weizmann signed the agreement on behalf of the Zionist Organization, while Faisal signed on behalf of the short-lived Arab

Kingdom of Hedjaz.

Two weeks prior to signing the agreement, Faisal stated:

The two main branches of the Semitic family, Arabs and Jews, understand one another, and I hope that as a result of interchange of ideas at the Peace Conference, which will be guided by ideals of self-determination and nationality, each nation will make definite progress towards the realization of its aspirations. Arabs are not jealous of Zionist Jews, and intend to give them fair play and the Zionist Jews have assured the Nationalist Arabs of their intention to see that they too have fair play in their respective areas. Turkish intrigue in Palestine has raised jealousy between the Jewish colonists and the local peasants, but the mutual understanding of the aims of Arabs and Jews will at once clear away the last trace of this former bitterness, which, indeed, had already practically disappeared before the war by the work of the Arab Secret Revolutionary Committee, which in Syria and elsewhere laid the foundation of the Arab military successes of the past two years.

[12]

The areas discussed were detailed in a letter to Felix Frankfurter, President of the Zionist Organisation of America, on 3 March 1919, when Faisal wrote :

"The Arabs, especially the educated among us, look with the deepest sympathy on the Zionist movement. Our deputation here in Paris is fully acquainted with the proposals submitted yesterday by the Zionist Organization to the Peace Conference, and we regard them as moderate and proper."

[13]

The proposals submitted by the Zionist Organization to the Peace Conference were:

"The boundaries of Palestine shall follow the general lines set out below: Starting on the North at a point on the Mediterranean Sea in the vicinity South of

Sidon and following the watersheds of the foothills of the

Lebanon as far as Jisr el Karaon, thence to El Bire following the dividing line between the two basins of the Wadi El Korn and the Wadi Et Teim thence in a southerly direction following the dividing line between the Eastern and Western slopes of the

Hermon, to the vicinity West of Beit Jenn, thence Eastward following the northern watersheds of the Nahr Mughaniye close to and west of the Hedjaz Railway. In the East a line close to and West of the

Hedjaz Railway terminating in the

Gulf of Akaba. In the South a frontier to be agreed upon with the Egyptian Government. In the West the Mediterranean Sea.

Text of the Agreement

Agreement Between Emir Feisal and Dr. Weizmann[16]

3 January 1919

His Royal Highness the Emir Feisal, representing and acting on behalf of the Arab Kingdom of Hedjaz, and Dr. Chaim Weizmann, representing and acting on behalf of the Zionist Organization, mindful of the racial kinship and ancient bonds existing between the Arabs and the Jewish people, and realizing that the surest means of working out the consummation of their natural aspirations is through the closest possible collaboration in the development of the Arab State and Palestine, and being desirous further of confirming the good understanding which exists between them, have agreed upon the following:

Articles:

The Arab State and Palestine in all their relations and undertakings shall be controlled by the most cordial goodwill and understanding, and to this end Arab and Jewish duly accredited agents shall be established and maintained in the respective territories.

Immediately following the completion of the deliberations of the Peace Conference, the definite boundaries between the Arab State and Palestine shall be determined by a Commission to be agreed upon by the parties hereto.

In the establishment of the Constitution and Administration of Palestine, all such measures shall be adopted as will afford the fullest guarantees for carrying into effect the British Government's Declaration of the 2nd of November, 1917.

All necessary measures shall be taken to encourage and stimulate immigration of Jews into Palestine on a large scale, and as quickly as possible to settle Jewish immigrants upon the land through closer settlement and intensive cultivation of the soil. In taking such measures the Arab peasant and tenant farmers shall be protected in their rights and shall be assisted in forwarding their economic development.

No regulation or law shall be made prohibiting or interfering in any way with the free exercise of religion; and further, the free exercise and enjoyment of religious profession and worship, without discrimination or preference, shall forever be allowed. No religious test shall ever be required for the exercise of civil or political rights.

The Mohammedan Holy Places shall be under Mohammedan control.

The Zionist Organization proposes to send to Palestine a Commission of experts to make a survey of the economic possibilities of the country, and to report upon the best means for its development. The Zionist Organization will place the aforementioned Commission at the disposal of the Arab State for the purpose of a survey of the economic possibilities of the Arab State and to report upon the best means for its development. The Zionist Organization will use its best efforts to assist the Arab State in providing the means for developing the natural resources and economic possibilities thereof.

The parties hereto agree to act in complete accord and harmony on all matters embraced herein before the Peace Congress.

Any matters of dispute which may arise between the contracting parties hall be referred to the British Government for arbitration.

Given under our hand at London, England, the third day of January, one thousand nine hundred and nineteen

Chaim Weizmann Feisal Ibn-Hussein

Reservation by the Emir Feisal

If the Arabs are established as I have asked in my manifesto of 4 January, addressed to the British Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, I will carry out what is written in this agreement. If changes are made, I cannot be answerable for failing to carry out this agreement.

Implementation

Faisal conditioned his acceptance on the fulfillment of British wartime promises to the Arabs, who had hoped for independence in a vast part of the

Ottoman Empire. He appended to the typed document a hand-written statement:

"Provided the Arabs obtain their independence as demanded in my [forthcoming] Memorandum dated the 4th of January, 1919, to the Foreign Office of the Government of Great Britain, I shall concur in the above articles. But if the slightest modification or departure were to be made [regarding our demands], I shall not be then bound by a single word of the present Agreement which shall be deemed void and of no account or validity, and I shall not be answerable in any way whatsoever."

The Arabs did obtain their independence and the Faisal-Weizmann agreement survived only more than a few months. The decision of the

peace conference itself refused independence for the vast Arab-inhabited lands that Faisal desired, mainly because the British and French had struck their own secret

Sykes–Picot Agreement of 1916 dividing the Middle East between their own

spheres of influence. With the conference deciding on the

mandate system for all areas of the former Ottoman Empire, prior to statements from either the Zionist or Arab sides, Faisal soon began to express doubts about cooperation with the Zionist movement. After Faisal was expelled from Syria and given the

Kingdom of Iraq, he contended that the conditions he appended were not fulfilled and the treaty therefore moot.

St. John Philby, a British representative in Palestine, later stated that

Hussein bin Ali, the

Sharif of Mecca and King of Hejaz, on whose behalf Faisal was acting, had refused to recognize the agreement as soon as it was brought to his notice.

[17] However, Sharif Hussein formally endorsed the

Balfour Declaration in the

Treaty of Sèvres of 10 August 1920, along with the other

Allied Powers, as King of Hedjaz.

The United Nations Special Committee On Palestine did not regard the agreement as ever being valid,

[18] while Weizmann continued to maintain that the treaty was still binding. In 1947 Weizmann explained :

"A postscript was also included in this treaty. This postscript relates to a reservation by King Feisal that he would carry out all the promises in this treaty if and when he would obtain his demands, namely, independence for the Arab countries. I submit that these requirements of King Feisal have at present been realized. The Arab countries are all independent, and therefore the condition on which depended the fulfillment of this treaty, has come into effect. Therefore, this treaty, to all intents and purposes, should today be a valid document".

[19]

According to C.D. Smith, the Syrian National Congress had forced Faisal to back away from his tentative support of Zionist goals.

[20] According to contemporaries, including Gertrude Bell and T. E. Lawrence, the French, with British support, betrayed Faisal and the Arab cause rendering the treaty invalid. Georgina Howell, 2006,

Gertrude Bell: Queen of the Desert, Shaper of Nations.

Sat, Nov 27, 2010 | Edited by Crethi Plethi

Emir Faisal Ibn Hussein, son of Sharif Husayn of Mecca, leader of the Arab revolt against the Ottoman rule in the Middle East

Faisal-Frankfurter Correspondence At the Paris Peace Conference, 1919

Following World War I, the Emir Faisal Bin Hussein [son of Husayn, Sharif of Mecca] signed an

agreement as part of the 1919 Paris Peace Conference with Dr. Chaim Weizmann in support of a Jewish homeland in Palestine and an Arab nation in a large part of the Middle East.

Following this [Faisal-Weizmann] Agreement, Emir Faisal exchanged letters with Judge Felix Frankfurter [who served as a Zionist delegate of the American delegation to the Paris Peace Conference].

In these letters Faisal expresses his support for the Jewish nationalist movement and the Jewish claims for a homeland in Palestine.

Letter from His Royal Highness Emir Faisal Ibn Hussein, Son of Husayn Ibn Ali, Sharif of Mecca, to Judge Felix Frankfurter, associate of Dr. Chaim Weizmann:

DELEGATION HEDJAZIENNE

Paris Peace Conference

March 3, 1919

Dear Mr. Frankfurter,

I want to take this opportunity of my first contact with American Zionists to tell you what I have often been able to say to Dr. Weizmann in Arabia and Europe.

We feel that the Arabs and Jews are cousins in having suffered similar oppressions at the hands of powers stronger than themselves, and by a happy coincidence have been able to take the first step towards the attainment of their national ideals together.

The Arabs, especially the educated among us, look with the deepest sympathy on the Zionist movement. Our deputation here in Paris is fully acquainted with the proposals submitted yesterday by the Zionist Organisation to the Peace Conference, and we regard them as moderate and proper. We will do our best, in so far as we are concerned, to help them through: we will wish the Jews a most hearty welcome home.

With the chiefs of your movement, especially with Dr. Weizmann, we have had and continue to have the closest relations. He has been a great helper of our cause, and I hope the Arabs may soon be in a position to make the Jews some return for their kindness. We are working together for a reformed and revived Near East, and our two movements complete one another. The Jewish movement is national and not imperialist. Our movement is national and not imperialist, and there is room in Syria for us both. Indeed I think that neither can be a real success without the other.

People less informed and less responsible than our leaders and yours, ignoring the need for co-operation of the Arabs and Zionists have been trying to exploit the local difficulties that must necessarily arise in Palestine in the early stages of our movements. Some of them have, I am afraid, misrepresented your aims to the Arab peasantry, and our aims to the Jewish peasantry, with the result that interested parties have been able to make capital out of what they call our differences.

I wish to give you my firm conviction that these differences are not on questions of principle, but on matters of detail such as must inevitably occur in every contact of neighbouring peoples, and as are easily adjusted by mutual good will. Indeed nearly all of them will disappear with fuller knowledge.

I look forward, and my people with me look forward, to a future in which we will help you and you will help us, so that the countries in which we are mutually interested may once again take their places in the community of civilised peoples of the world.

Believe me,

Yours sincerely,

(Sgd.) Faisal

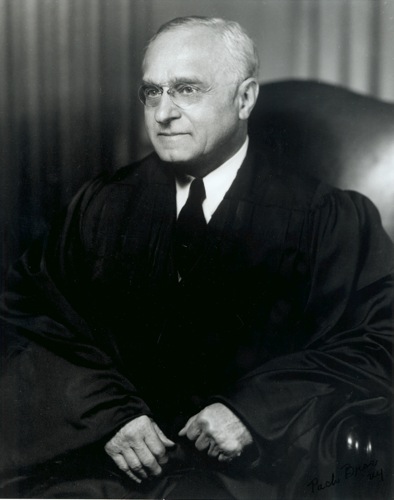

Judge Felix Frankfurter

Letter of reply from Judge Felix Frankfurter to Emir Faisal Ibn Hussein:

Paris Peace Conference

March 5, 1919

Royal Highness,

Allow me, on behalf of the Zionist Organisation, to acknowledge your recent letter with deep appreciation.

Those of us who come from the United States have already been gratified by the friendly relations and the active cooperation maintained between you and the Zionist leaders, particularly Dr. Weizmann. We knew it could not be otherwise; we knew that the aspirations of the Arab and the Jewish peoples were parallel, that each aspired to re-establish its nationality in its own homeland, each making its own distinctive contribution to civilisation, each seeking its own peaceful mode of life.

The Zionist leaders and the Jewish people for whom they speak have watched with satisfaction the spiritual vigour of the Arab movement. Themselves seeking justice, they are anxious that the just national aims of the Arab people be confirmed and safeguarded by the Peace Conference.

We knew from your acts and your past utterances that the Zionist movement — in other words the national aim of the Jewish people — had your support and the support of the Arab people for whom you speak. These aims are now before the Peace Conference as definite proposals by the Zionist Organisation. We are happy indeed that you consider these proposals “moderate and proper,” and that we have in you a staunch supporter for their realization.

For both the Arab and the Jewish peoples there are difficulties ahead — difficulties that challenge the united statesmanship of Arab and Jewish leaders. For it is no easy task to rebuild two great civilizations that have been suffering oppression and misrule for centuries. We each have our difficulties we shall work out as friends, friends who are animated by similar purposes, seeking a free and full development for the two neighboring peoples. The Arabs and Jews are neighbors in territory; we cannot but live side by side as friends.

Very respectfully,

(Sgd.) Felix Frankfurter

Arab–Israeli peace diplomacy and treaties

British Mandate for Palestine

ARTICLE 95.

The High Contracting Parties agree to entrust, by application of the provisions of Article 22, the administration of Palestine, within such boundaries as may be determined by the Principal Allied Powers, to a Mandatory to be selected by the said Powers. The Mandatory will be responsible for putting into effect the declaration originally made on November 2, 1917, by the British Government, and adopted by the other Allied Powers, in favour of the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.